'American War' sheds new light on our current conflicts

American War should be required reading amid the continued tragedy of the global war on terror. Omar El Akkad's first novel combines the horrors of modern sectarian warfare with tropes from American history to create a horrific blend of speculative violence and social breakdown.

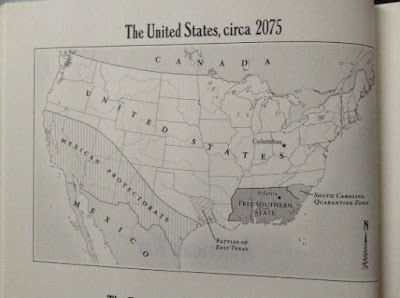

In El Akkad's vision of the future, the last decades of the 21st century are defined by a second American civil war. Northern states are again fighting Southern secessionists, but this time all the horrors of modern conflict are brought to bear upon familiar locations and current political issues. In this new American war, violent political cleavage falls not along issues of race but rather climate change and energy policy. Global warming has fundamentally disrupted American society. Coastal cities and regions are flooded (all of Florida is gone), forcing massive resettlement and dramatic economic interventions. Radical climate-change mitigation policies are the basis of the dispute: Southerners atavistically refuse to stop using fossil fuels, and an internecine war breaks out across an already-shattered nation.

But these critiques miss the point of El Akkad's use of dystopia. American War is not so much a speculative American future as it is a fabulist re-envisioning of the original Civil War to translate the global war on terror into an American idiom. El Akkad sacrifices a bit of dystopic realism to keep the former United States recognizable. By recreating the war on terror on American soil, El Akkad allows us to see the results of our interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq through the light of our own culture and place. All the characters are American; as readers we are never inclined to pick either side as right or "just." Instead we only know the functional result of sectarian war. We watch the violence that drives thousands into refugee camps, the Manichean worldview that turns young boys into jihadists, the vengeful brutalism that drives folks to murder their neighbors.

|

| Aftermath of the Ashoura Day attacks in Kabul, 2011. Reuters. |

“The new kindergarten teacher accidentally read the girl’s middle

initial as the last letter of her first name—Sarat. To the little girl’s

ears, the new name had a bite to it. Sara ended with an impotent exhale,

a fading ahh that disappeared into air. Sarat snapped shut like a bear

trap.”

At first Sarat reminds us of recent protagonists in young adult dystopia, similar to the plucky female lead of Katniss Everdeen from "The Hunger Games." But her path takes a more realistic turn in a story about civil violence and insurgency. She becomes a terrorist. We watch Sarat experience family members killed as bystanders to military strikes. We feel the bewildered fog of war that blinds families fleeing toward refugee camps. We wince at the insecure masculinity permeating militia groups. And we cringe at how systemic violence strips away an individual's layers of humanity.

American War is at its most striking when it allows us to empathize, indeed sympathize, with the terrorist. We view the world through her eyes. We see in stark exposition the sorts destruction, malice, and tribalism that drive people to retributive violence. The story discards the facile simplification of terrorists as "bad dudes" or "losers," and it forces us to reckon with the broader processes that create trajectories of violence. When an atrocity rips apart the refugee camp where Sarat lives, we feel a warm glow of justice that she can enact a modicum of vengeance on a young man in the opposing militia. But that glow is quickly dispelled by viscera of the moment:

“A cascade of blood erupted from where she’d cut him open. She pinned

him down and kept slashing, the neck slippery now with blood. Soon the

man stopped fighting, but she kept moving the knife back and forth, back

and forth, until she hit something deep within the body she could not

sever. She screamed.”

This most primal of moments is a reminder that the use of war as a means of constraining ideas only continues cycles of violence. Massacre for massacre. Rape for rape. Atrocity for atrocity.The horror here is the realization that we Americans have created these exact conditions in the Middle East. Our policies have created sectarian nihilism, our military has broken entire societies down to Hobbesian states of brutality. As one character puts it with quiet verve, "Everyone fights an American war."

This translation of recent Middle Eastern history into an American idiom does make the narrative forced and predictable. There are clunky interjections of primary sources, which provide unneeded context. The conversion of Syrian and Iraqi militias into a Southern form does not quite work. And El Akkad telegraphs so blatantly how Sarat’s life will culminate that elements of the story are almost presumed. Sarat inevitably experiences horrific torture at an offshore military prison, an obvious reference to the grotesqueries of Guantánamo Bay. She’s subjected to light/sound torture and forced feeding. She’s made to live stooped in a cage. She’s treated like an animal.

Since American War has been understood as a dystopic novel, I found myself making comparisons to Room 101, the torture chamber in George Orwell’s 1984. In Orwell’s novel, the scenes are so catastrophic to read because Winston’s very reality is besieged. Torture undermines Winston's sense of moral and political compass. We’re invested in his struggle and suffer with him as he is forced to betray his most basic idea of the world. But when Sarat is tortured the interweaving of developed characters and relationships is missing. No ideology is at stake, only the tribe of South vs. the tribe of North. So the climatic moment of ruinous, character-breaking torture falls flat.

But this is perhaps intended. Anyone who has paid attention to the world knows where modern war leads. We've all seen in Manchester and Paris and London the long-term result of Operation Iraqi Freedom and Abu Ghraib. We've watched in Syria and Yemen and Afghanistan the outcome of bombing missions in the name of peace. By reading American War the reader is merely rehearsing both past and future. All of these interlinking chains of violence were, and will be, inevitable.

~ ~ ~

You can listen to a discussion with Omar El Akkad on KQED's Forum.

Follow me on Twitter.

Wishing good fortune to everyone who comes across this comment! I went bankrupt last year due to failed business ideas. I used to enjoy playing the lottery for fun but as my situation worsened financially, I sought help to win big this time and found a man called MEDUZA, who has assisted numerous individuals worldwide with their financial issues. This man prepared a powerful spell for me that enabled him to get the secrete lucky numbers for me, I played the game with the numbers and to my astonishment, I discovered that I had won $259 million Jackpot after 2 weeks just has he said; Today, I’m now free of debt and I own different investments globally. Without Meduza, I wouldn’t have made it through the tough times I experienced last year. Truly, MEDUZA is a divine presence among us. If you are currently struggling in aspect of your life, reach out to MEDUZA through the below information's.

ReplyDeleteWhats-App: +1 807 798 3042

Email: lordmeduzatemple@hotmail.com

Face-book Page: Lordmeduza